A crisis such as the Covid-19 pandemic creates a perfect opportunity for those who wish to cause confusion, chaos and public harm by spreading mis- and disinformation. This week we look at a milestone for Real411, what it means and what the trends are.

Media Monitoring Africa has been tracking disinformation trends on digital platforms since the end of March. Using the Real411 platform we have analysed disinformation trends which have largely focused on Covid-19. To date, 1,057 complaints have been submitted to the platform, 97% of which have been assessed by experts and action taken.

Many complaints continue to target Covid-19 information. We see peaks and troughs of Covid-19-related mis/disinformation, usually peaking when we have official statements, additional or new information, or addresses by public officials. This trend was apparent during this past week when many complaints related to what Covid-19 regulations President Cyril Ramaphosa would address when he spoke to the nation on 2 December. An example of this is complaint #1,125 (shown below), which relates to a WhatsApp message going around stating that the president would announce an alcohol ban.

We have been so busy looking at the trends over the past few weeks and responding to issues we forgot to highlight something really special – Real411 has assessed more than 1,000 complaints. We think that is quite a big deal. Here’s why:

For starters, it is 1,000 complaints about content on digital media where, as the public, we know what the complaint was about and what the outcome is. Anyone can go to the Real411 website and look through all the complaints received. They can see a summary of the issue and reasons for the final outcome. If anyone is dissatisfied with an outcome they can lodge an appeal, which will be heard by former Deputy Chief Justice Zak Yacoob. There is immense value in this process.

One of the core reasons we started Real411 is that previously if you wanted to complain about online content your only option was to submit it to the platform on which it appeared. There are a number of limitations to this.

First, each platform tends to have its own processes, rules and community standards or guidelines. We saw during the recent US elections how the same content might be removed from Twitter but be allowed on Facebook. So, Steve Bannon’s call for the beheading of Dr Anthony Fauci was banned by Twitter but the same content was allowed to remain on Facebook.

When looking at content, context, including the platform, is important. If, for example, you sing in your shower about a desire to behead a public official, it isn’t intended for public consumption. Doing the same thing in a crowded room will have a very different impact. Saying stuff on Twitter or Facebook or any popular social media channel is pretty much the same as standing up in a crowded room and saying it. Context matters, but the same content must be assessed using the same principles. Reporting content directly to a platform prevents that from happening. However, having different standards across platforms is confusing and fundamentally unfair.

The second challenge is that even if you accept that the platforms apply different standards, frameworks and principles, none of them speak directly to African and South African rights-based principles.

At the start of 2016, Penny Sparrow became a household name when she compared black people to monkeys. At the time this wasn’t considered a violation of some of the social media’s community guidelines. Of course, in South Africa, such racist comparison has a deep and painful history, so it immediately resulted in an expression of hurt and anger, so much so that it made international headlines. For the majority of South Africans, it seemed obvious (except perhaps to the oblivious and racists) that such a comparison was unacceptable.

Social media behemoths based in the North took some time to realise and appreciate the harm and then to amend their policies. It is to their credit that they have amended them. The concern, however, remains that our laws and Constitution set the boundaries and norms for how our society operates. A complaint to one of the social media entities is not assessed according to our norms and standards but by ones determined in corporate headquarters.

South Africa’s laws and Constitution adhere to fundamental human rights and emphasise dignity and equality. Other nations don’t, and the social media behemoths offer a potentially more liberating space for those nations.

Even if we ignore the different systems and processes on different platforms, determined by corporations, not public processes, there is another hurdle. The processes that are followed on many of the social media platforms are not clear and are not subject to public oversight. In the past few years, the big companies have been releasing increasingly more useful transparency reports (Twitter, Facebook and Google) about what happens on their services, but they don’t offer much detail about actual complaints.

Also, complaints that are received are determined as either violating or not violating the platform’s standards, and the ability to appeal, in most instances, is highly limited. All that most complainants are likely to receive is a private notification that the content they complained about either violated the community guidelines or it didn’t. The ability of the public to learn and be more informed is thus profoundly hampered.

The playing fields are not even. Our media (print and broadcast) adhere to certain standards. For print and online media, the overwhelming majority agree to adhere to principles and guidelines overseen by the Press Council. A comprehensive process is outlined for complaints, all rulings are made public, and there is an appeals mechanism.

Broadcasters also have a code of conduct and a process for the submission of complaints, the Broadcast Complaints Commission of South Africa (BCCSA), and there is also an appeals process. So, the overwhelming majority of publishers have to adhere to common standards and the complaints are public as are the outcomes. But social media platforms were being held to separate, unaccountable and significantly less transparent systems and processes – until Real411 began.

That Real411 has resolved more than 1,000 complaints shows that the system works and that there is a clear need for the system. Of course, there are challenges, and we are working to improve the system and we welcome constructive feedback. We are in the process of enabling a trends page so that the public can see the general trends in the complaints. It is worth highlighting three trends.

1. Not all platforms are equal

If we look at the spread of complaints across the platforms, we see that 38% of complaints are about content on Twitter, 24% on WhatsApp and 19% on Facebook. Content on other websites accounts for 10% of complaints – these are sites that are not part of South Africa’s Press Council or BCCSA members; some deal with extremist content, some might be phishing sites.

2. Disinformation is not evenly spread

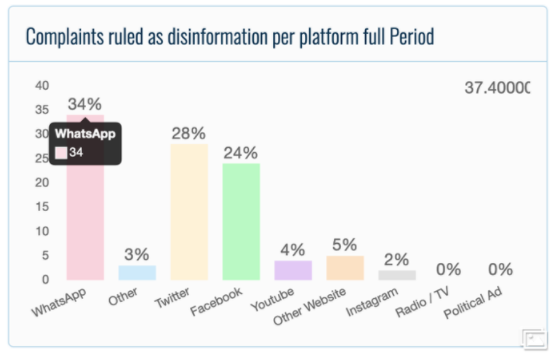

If we compare the complaints against the results of complaints where content was found to be disinformation, we see the following: WhatsApp has the most complaints where the content reported was actually found to be disinformation (34%), followed by Twitter at 28% and Facebook at 24%. What the findings suggest is that the platform with the highest levels of mis- and disinformation is WhatsApp. This isn’t surprising, especially when it is considered how easy it is to share unverified graphics and content – like audio clips of “doctors” telling us alarming things.

3. There is a lot of dodgy information that is not necessarily mis- or disinformation

If we look at the complaints that were reported as potentially mis- or disinformation, we see that the majority are not found to be mis- and disinformation. The complaint about a tweet by the Kiffness, for example, met some of the criteria, but because it was satire it was found not to be disinformation (more here). When we look at the ratio during the height of the hard lockdown, 52% of complaints submitted as being mis- or disinformation were actually found to be disinformation – which might suggest higher levels of misinformation were going around at the time.

There is still so much we don’t know, but at least now we can start to look at the data, work with experts and help unpack and try to find answers to questions about how much disinformation there is, where it occurs, who is spreading it and how well we understand what is and isn’t disinformation. We can also look at the other digital evils around incitement to violence and hate speech, and we can look at the intersection of these with disinformation. All these avenues are opening up thanks to Real411.

If you come across potential disinformation, hate speech, incitement to violence or the harassment of journalists online, please report it to www.real411.org.za. If you have an iPhone you can download the app from the iTunes store. (The Android version is coming soon.) DM

Read the full article HERE